GOOD NEIGHBOR

When the USA Had a More Benign Approach to Its Neighbours

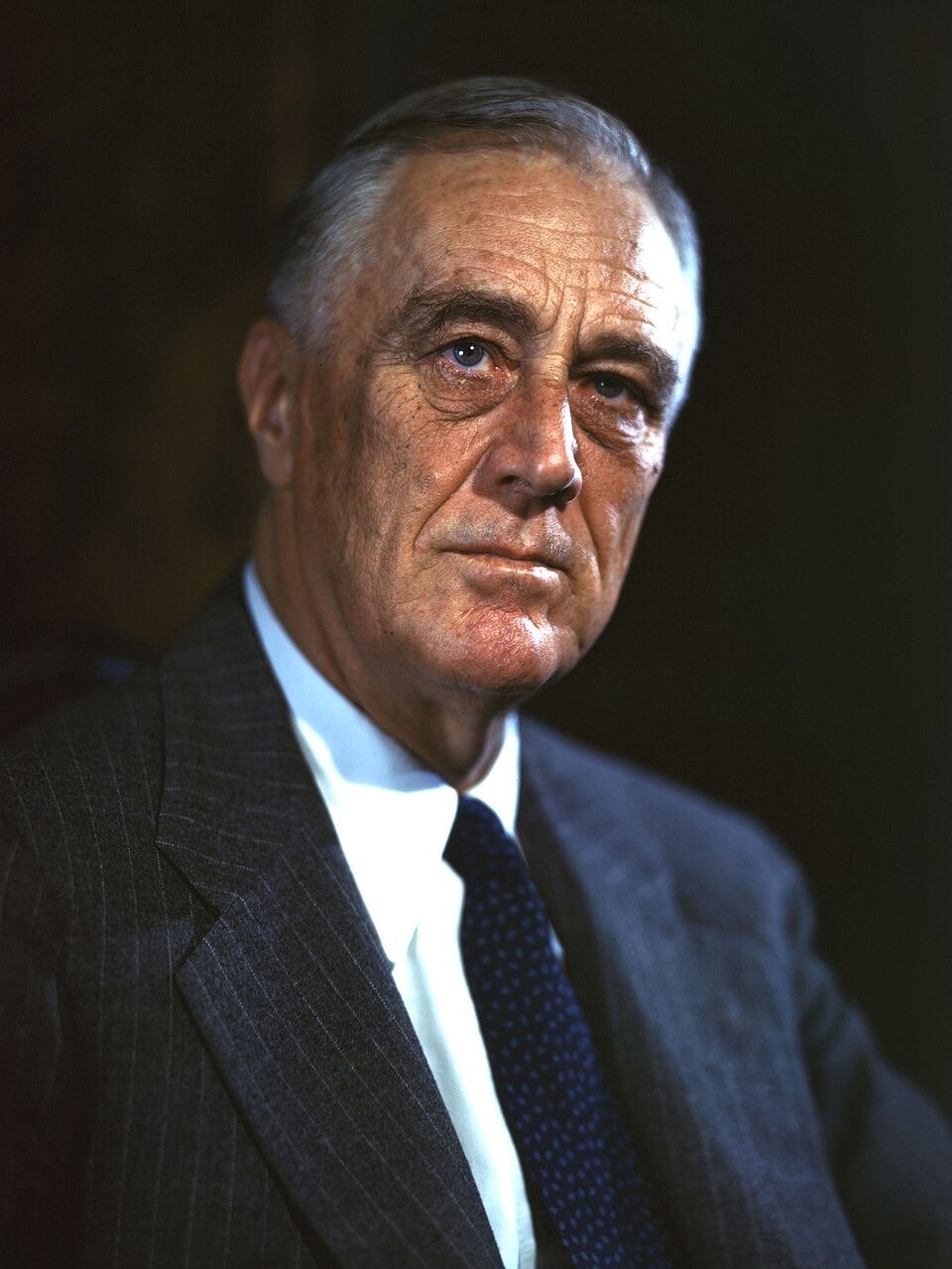

It was a cold, windy, grey day in Washington DC on 4th March 1933, the day Franklin D. Roosevelt was sworn in as President of the United States. Wearing a morning suit and top hat, Roosevelt was escorted gingerly the rostrum, at the east front of the Capitol, by his son, James. Having been struck down by polio over ten years earlier, Roosevelt had been paralysed from the waist down and could only walk with the greatest of difficulties and by strapping metal callipers to his legs. Although it was a fifty yard walk, however, he had been determined to make it and not begin his presidency from a wheelchair. And make it he did, albeit a little stiffly.

Having completed his solemn oath he then turned to the crowd of more than 150,000 facing the Capitol and tens of millions more listening on the radio, and began his inaugural address. The United States had been reeling since the dark days of October 1929; until then, while the rest of modern world struggled to overcome the ravages - both economic and physical - of the Great War of 1914-18, America had become rich. The 1920s had been a time of astonishing growth, with the advent of the mass-market automobile and plentiful American oil. Towns had grown and spread, so too had roads as America boomed. There was plenty of work, lots of money to be made, and with it came credit - too much credit. Banks lacking legislation were lending more than was in their vaults and so, when the bubble burst with the Wall Street Crash in October 1929, the collapse was both considerable and protracted.

The United States had wanted to turn inwards, and pursue a more isolationist strategy but it was the richest nation in the world. The Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of May 1930 was designed to protect the US market but had catastrophic consequences around the world: a global trade war was no way to get any nation out of the economic mire of the Great Depression, least of all the United States itself.

As he stood addressing the nation, Roosevelt was very aware that a dramatic change of tack was needed if America was to re-emerge as the economic powerhouse it was destined to become once more. It was time, he told the American people, to speak the truth, both frankly and boldly. Their great nation would revive and prosper. ‘So, first of all,’ he said in his patrician, East Coast, tones, ‘let me assert my firm belief that the only thing we have to fear is fear itself.’ As he went on to point out, plenty remained on their doorstep and the perils they faced now were not as terrifying as those of their forebears. What was needed was a sense of national effort and plenty of action right away. People needed to get back to work; new laws needed to be put in place to ensure no crash such as the one they had experienced could ever happen again, and he intended to get going right away.

There was, however, another, critical, pledge he made. ‘In the field of world policy,’ he added, ‘I would dedicate this Nation to the policy of the good neighbor – the neighbor who resolutely respects himself and, because he does so, respects the rights of others – the neighbor who respects his obligations and respects the sanctity of his agreements in and with a world of neighbors.’

This was a firm signal not only of Roosevelt’s future path with regard to foreign policy but also his own world view. To his core, FDR was an internationalist, despite having won the election on an isolationist ticket. And while a new President brought renewed hope, his inauguration came at a time of further collapse. There was two thirds less money in America than there had been before the Crash, more banks were collapsing and a fresh panic convulsed the country in February 1933. Most expected Roosevelt to do a worse job than his predecessor, Herbert Hoover, the majority of Americans looked to him and his new presidency with little confidence.

Yet, Roosevelt’s first Hundred Days brought first, a sense of real hope, then renewed trust in their executive leader, and with it, a rise in confidence. Roosevelt believed himself to be a man of vision and destiny – just as in Germany the new Chancellor, Adolf Hitler, also believed himself to be. The great difference, however, was that Roosevelt had a profound desire to help steer America towards a better future, one that he felt certain he could achieve. And he wasted absolutely no time. In five days, a banking bill was ready and rushed through in just eight hours of debate. Eight days into his presidency, he broadcast his first Fireside Chat on the radio. Radios were still something comparatively new, but FDR became a master of this new form of media. He had a calming, soothing voice, and now spoke to the nation like a family friend, using terms and analogies so that everyone could clearly understand what he was saying. First up, he announced the Federal Banks would be reopening the following day and that thanks to his Emergency Banking Act, cash held there would be safe. The day after, deposits exceeded withdrawals, stock prices rose by 15% and $1 billion returned to the vaults over the ensuing weeks. It was the start of what became the New Deal.

While Roosevelt was overturning prohibition and the Smoot-Hawley tariff act and also introducing a raft of new public works initiatives and social services for the first time, he also never lost sight of the pledge he’d made during his first inaugural address to forge a Good Neighbor Policy towards the rest of the Americas and especially Latin America.

The United States’ relations with Latin America had been bullying, overbearing, and, frankly, imperialist in outlook. The Monroe Doctrine, articulated by President James Monroe back in 1823, claimed that the Americas were for Americans only and that the United States would no longer tolerate European influence and interference. In reality, however, it meant the US dominating its neighbours with growing aggression and condescension. Latin Americans were widely perceived to be racially inferior, handicapped by a succession of authoritarian, corrupt and backward leaders, and with a climate not conducive to progress. From the late 1890s under President McKinley, through the presidency of Teddy Roosevelt to even the progressive Woodrow Wilson, US policy had been to regularly intervene. McKinley’s war with Spain in 1898 saw American troops invade Cuba as well as take the Philippines in South-East Asia. Theodore Roosevelt then introduced the so-called ‘Roosevelt Corollary’, announcing that the United States could intervene in the affairs of Latin American countries if they thought such intervention was needed. In reality, this was a licence to flex military muscles if the US felt its debts were not being paid swiftly or if American business interests were being threatened, or access to resources impeded.

And the United States repeatedly did apply the Corollary. Wilson sent troops into Mexico in 1914, to Haiti the following year, the Dominican Republic in 1916, to Cuba in 1917 and repeatedly again in Mexico. The later World War II general, George S. Patton, for example, led the first ever US motorised operation during the Pancho Villa Expedition into Mexico in 1916. For much of Wilson’s administration, American troops also occupied Nicaragua, having installed a president of their choice who would continue to sign treaties favourable to the United States. Americans convinced themselves they were brining modernity, prosperity and civilization to these backward folks, but they were kidding no-one.

Nor was it just military intervention but also financial ‘dollar diplomacy.’ Senate hearings that began in 1933 to investigate the lending practices of New York’s financiers during the 1920s revealed shocking levels of greed and corruption associated with Wall Street loans to South America.

FDR was now determined to pursue an entirely different and far more progressive and enlightened path. At the Montevideo Convention in December 1933, Cordell Hull, Roosevelt’s Secretary of State, backed a declaration that, ‘No state has the right to intervene in the internal or external affairs of another.’ That same month, FDR also backed up the declaration. ‘The definite policy of the United States from now on,’ he announced, ‘is one opposed to armed intervention.’ In quick order, US Marines were withdrawn from Haiti, and the Platt Amendment overturned an aggressive intervention treaty with Cuba originally signed in 1903. At an inter-America conference in Buenos Aires in December 1936, FDR effectively made his debut on the international stage, and used his speech to promote democracy and higher living standards throughout Latin America. ‘Men and women,’ he said, ‘blessed with political freedom, willing to work and able to find work, rich enough to maintain their families and to educate their children, contented with their lot in life and on terms of friendship with their neighbors will defend themselves to the utmost but will never consent to take up arms for a war of conquest.’ This was Roosevelt’s vision for a better world in a nutshell. Democracy would help to improved living standards, which would lead to greater political stability and, in turn, peace. A peaceful, stable Latin America would be easier to trade with than one in turmoil. This in turn would benefit the United States, both in terms of exports and imports.

Two issues were now coalescing in FDR’s mind: that the rise of authoritarianism posed a threat not just in Europe but also the free world, and that an advanced form of progressive democracy, championed by the United States, could and should be promulgated globally. A progressive democracy that eschewed imperialist ambitions, that rejected oppression. A form of democracy that offered greater economic as well as political equality. Greater prosperity would lead to greater political stability. Greater political stability would help the agents of peace. They were all connected. These were themes he had also raised six months earlier, in Philadelphia, on his nomination for a second term. ‘I cannot, with candor, tell you that all is well with the world,’ he told hist audience. ‘Clouds of suspicion, tides of ill-will and intolerance gather darkly in many places. In our own land we enjoy indeed a fullness of life greater than that of most nations. But the rush of modern civilization itself has raised for us new difficulties, new problems which must be solved if we are to preserve to the United States the political and economic freedom for which Washington and Jefferson planned and fought.’ He called upon his fellows to follow a higher moral purpose, in which every man had equality of rights but also of the market place. ‘Here in America,’ he told his audience, ‘we are waging a great and successful war. It is not alone a war against want and destitution and economic demoralization. It is more than that; it is a war for the survival of democracy. We are fighting to save a great and precious form of government for ourselves and for the world.’

A touch of political melodrama, perhaps, but he was quite right. Dark forces were massing, and the world would need a man of vision like Roosevelt. By the time he was sworn in a second time, having carried all but two states, another major war was once again looming.

Can’t imagine why you would bring this up …

Thank you, James.

A poignant reminder of a great, if flawed, man.

Is this a farewell to the Inter American System? Is the Organisation of American States now (even more of) a nullity? And, a corollary: is the United Nations, as a working agency for a rules-based international order, also a nullity?

I fear for my children and grandchildren in a world where the answer to each question in the previous paragraph is “yes”.

Where will the UK stand? I think we need some moral clarity from our Government. And quickly.