I was recently at a conference in Athens where a former British Chief of the Defence Staff warned us we were now in the foothills of World War Three. He may well have been right to say this. On the other hand, he might be entirely wrong, but I’m not sure the UK or any other country in the west should be complacent on this matter. It’s surely not worth taking the chance; at the very least we know there a number of world leaders out there who think ill of us and our western partners and would happily see us crushed given half the chance. The key, really, in the short to medium term, is for NATO and the west to show enough unity and military and economic strength to make any potential enemies think again. Unfortunately, the ultimate deterrent – nuclear weapons – is not really a deterrent any more because a number of countries have them and if one was ever fired in anger, that would very likely be the rapid end of the world. Or, to put it another way: if a British submarine commander had his finger hovering over the red button, we would have already lost.

The answer is to have a strong enough conventional deterrent to make our enemies unlikely to want to take the risk or going to war. This is unquestionably the best way to ensure ongoing and lasting peace. Reading through predictions about Britain’s latest forthcoming strategic defence review, however, it’s clear very little is going to be happening any time soon to rectify the much-reduced scale of the UK’s armed forces. The Royal Navy is going to continue to shrink, the Army is already below strength, we don’t have enough aircraft, recruitment has been outsourced to private companies, and it seems that almost all our current procurement projects are late and coming in over-budget. It’s reckoned we’d struggle to field a single brigade of a few thousand frontline troops effectively let alone a division. France has a larger armed forces than Britain but not by a huge amount while Germany’s is even smaller than that of the UK. So, if we are really in the foothills of World War Three, then this is hardly good news for Britain or for those in the west and NATO looking for greater collective impetus from the largest nations in Europe.

Inevitably, comparisons are being made with the 1930s. Back then, political upheaval followed financial catastrophe and much of Europe lurched to the right, albeit far further so than today. The well-trodden narrative is that Britain was late to the rearmament party and still badly playing catch-up when the war broke out in September 1939. Neville Chamberlain, the Prime Minister, threw the Czechs under the bus, appeasing Hitler in an effort to buy time. So, too, did the French. It then took the best part of six years to rid the world of the Nazis and the cruel imperial ambitions of the Japanese, and at the war’s end, tens of millions were dead, even more millions displaced and the world was changed forever.

It's true that Britain was not really ready for war in 1938 at the time of the Munich Crisis and it’s also true that then, as now, the vast majority of the population were not for war mongering or remotely willing to enter another European, let alone, world conflict. Yet, had Britain been far militarily stronger in 1938, would the war have ever begun in the first place? Would Hitler have gambled and invaded Poland? It’s impossible to know but it is worth considering just how Britain was placed in the late 1930s.

It was certainly the case that Britain had a small army. In 1936, it stood at just 192,325, a figure that fell further – slightly – the following year. There were also 141,000 members of the Territorial Army and a further 57,500 men in the British Indian Army. All were volunteers. These were comparatively small figures for a leading nation in the 1930s but it must be remembered that Britain’s situation was very different to that of France or Germany, for example. Britain was an island, not continental, nation, and one that lay at the heart of a huge global trading empire. Its military strategy was not an aggressive, land-grabbing one, but one designed to defend its sovereignty and global interests.

Nor did the small size of the army mean Britain was behind in terms of an armaments industry. Rather, in the first part of the decade, Britain had been the leading armaments producer in the world, most of which had been exported, but those factories – and their workers – had not vanished a few years later. Far from it, and Britain was well-placed for rapid expansion. Firms like Vickers Armstrong and its subsidiary, Vickers Aviation, as well as Hawker Siddeley, Rolls-Royce and de Havilland were among the largest industrial employers in the country and invested huge sums in research and development.

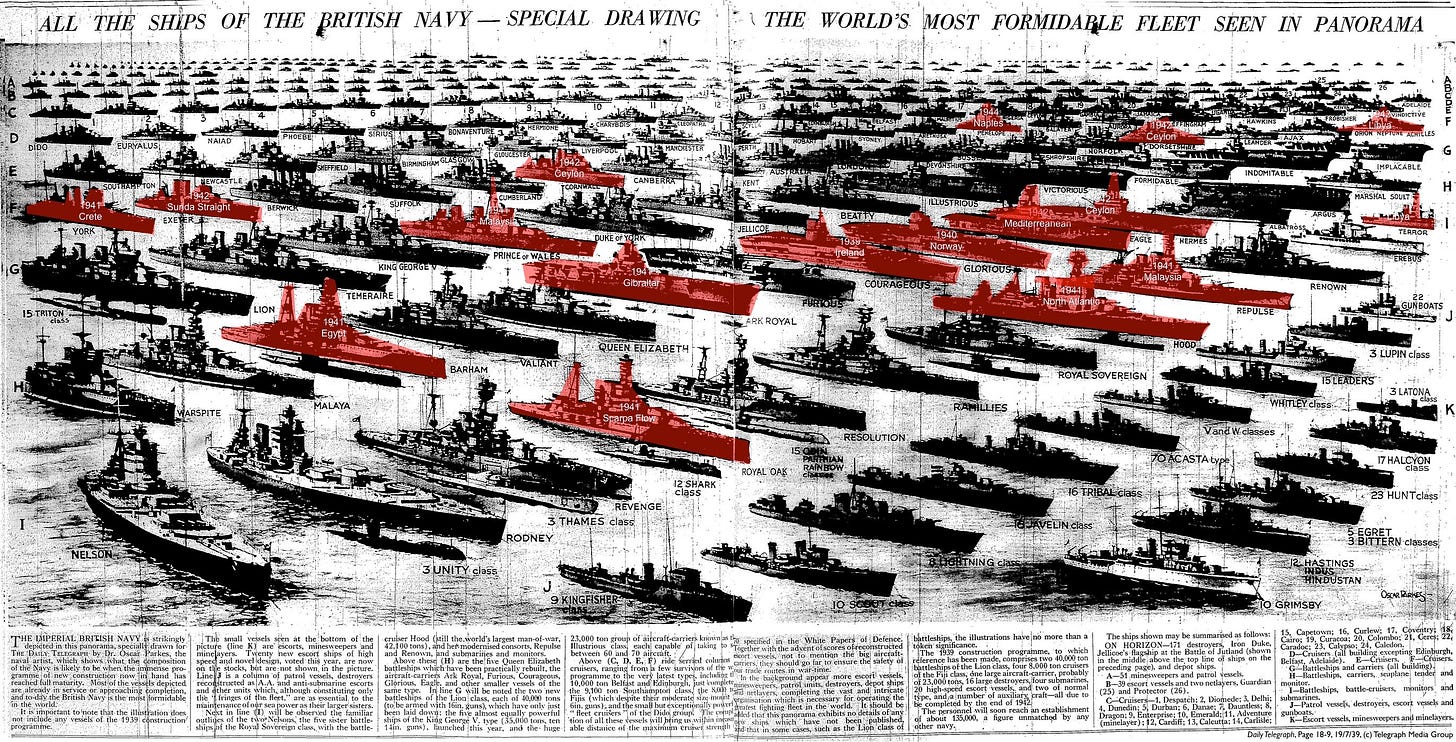

And before he was Prime Minister, Chamberlain had been Chancellor of the Exchequer and had instigated a huge upgrade of Britain’s warships and an even larger expansion of the Navy, working on the sound principle that it made good sense to undertake the largest projects – building modern warships – in a time of peace. In 1939, the Royal Navy was comfortably the world’s largest. Chamberlain had also been a powerful advocate of developing the Royal Air Force. It was largely down to him that by 1938, the RAF had two modern fighter planes in the Hawker Hurricane and Supermarine Spitfire, and as Chancellor, he had continued to oversee Britain’s further investment in the arms industry. Just because he had favoured appeasement in 1938, did not mean he was in any way slow to build up Britain’s military strength. It’s also worth noting that while the current British government says the UK cannot afford to rearm at the moment, Britain could not afford it in the 1930s either. They still did, however. By the outbreak of war, Britain also had the world’s first – and at the time only – fully co-ordinated and modern air defence system. If any government’s first objective is to protect the people it is governing, then the Baldwin and Chamberlain governments were doing all they could in the late thirties to ensure they were protected from the growing threat of the dictators.

There were also then, as now, logistical considerations that mitigated against a large army. If France or Germany wanted to move their millions of troops, they could put them on trains or into vehicles. If Britain planned to do the same, it had to transport the army by a vast armada of ships. And once oversees, it then had to be maintained, requiring even more ships. Nor was there much space to upkeep a large army within Britain itself. In other words, maintaining a large army in peacetime made little sense. Far better to focus on air and naval power for Britain’s defence, which was exactly what they did. In any case, by the outbreak of war, France was a formal ally and had an army capable of rapid expansion into millions of men.

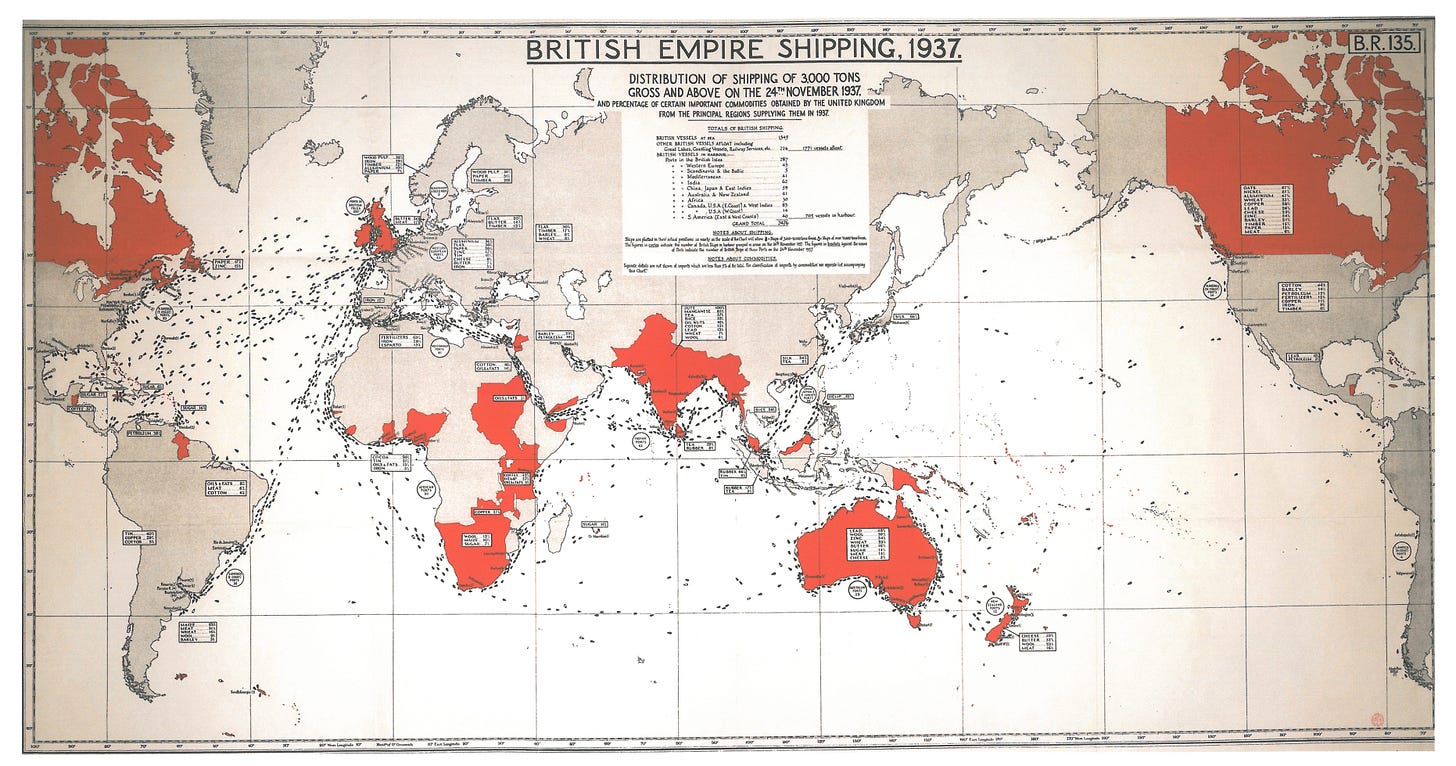

Britain also had the huge advantage of immense global reach. A map of world shipping from 1937 shows a number of ant lines of ships flowing around much of the globe and in and out of Britain. One of the strongest links from Britain is to Argentina in South America. This was not part of the empire, but the UK had considerable extra-imperial assets there; British companies owned much of Argentina’s port facilities, railways and ranches, for example. Companies with global reach meant a very strong purchasing power, most useful when buying much-needed ores and minerals once war broke out. I’ll write a bit about this in a later post, but the point is this: Britain might have had a small army in 1939 and an air force that was smaller than that of Nazi Germany’s Luftwaffe, but it had a very strong defensive military capability, and, crucially, the kind of wealth, internal industrial infrastructure and global reach that meant that when it did need to rapidly accelerate its rearming it was incredibly – and decisively - placed to do so.

I’m sure it’s all too obvious that we are not remotely in the same position today. Nothing can be built on time. Procurement projects sink under the weight of red tape, regulation, and catastrophic inefficiency. Joining the armed forces is largely unappealing due to the low wages, low morale, and the paring back of every aspect of military requirements and efficiency; there’s not enough kit, not enough ammunition, not enough aircraft, not enough ships, much of its day-to-day running is in the hands of private companies only interested in a profit. The purchasing of new helicopters two-and-a-half years ago, for example, was halted at the last moment because the MOD suddenly decided some competition was needed. It wasn’t. Two – foreign - firms who subsequently tendered for the contract then pulled out at the last minute, wasting valuable time, money an effort, and presumably had entered the bid in the first place only to undermine that of the original British firm. The RAF still doesn’t have any of these new helicopters. Really, it’s not only depressing but deeply worrying.

Poland, meanwhile, approaching 5% of GDP on defence, has the fastest growing economy in Europe. It’s the Keynesian model: rearming and boosting the economy at the same time. The Poles are proving this can still be done. Russia is war weary, no longer has the ballast of the Warsaw Pact countries and currently is not the threat that Nazi Germany was. But is it worth tempting Putin to invade the Baltic states and triggering Article 5? And doesn’t Trump have a point that we’re complacently overly dependent on the United States? World power is rapidly shifting, the US is turning to the Indo- Pacific, and Western Europe is politically weak and militarily vulnerable, even with our new NATO allies. The British government might argue we cannot afford to significantly rearm, but the cost would be as nothing should those foothills of World War Three develop into mountains.

Thanks for the interesting article. I was at an event in November where Radosław Sikorski spoke. Afterwards he took questions and one of them was, “is Europe ready to defend itself. I was struck by the absolute candour of his reply, he said “you can take that question two ways; willingness and readiness, and the answer to both is not really”

Good article James. I’d just add some context on contemporary British military workforce woes:

The issue is often couched in terms of people not wishing to join. This is actually a little bit of a misconception, as applicant interest in the Forces is reasonably high. The huge blocker to recruitment is the torturous process of joining the Forces, not helped by exceptionally poor practices by Capita and over-prescriptive medical requirements.

The other huge issue is retention - far more people leave than are joining, due to a whole host of issues. The recent boost to salaries by the Labour government was very welcome, but it is far more than a monetary problem. Keeping servicepeople in beyond their minimum terms of service is increasingly the most difficult task facing MOD personnel planning.