I was in touch with Brian Hemingway this week, son of John ‘Paddy’ Hemingway, and he told that his father would have been very tickled to have died on St Patrick’s Day, for while he flew for the RAF in the Battle of France and in the Battle of Britain over that extraordinary, world-changing summer of 1940, he remained a proud Irishman to the end. It’s traumatic to think that that those boys have now all gone, and that the Battle of Britain – from the pilot’s perspective – has slipped from living memory. I’ve been at home this week, and have been out with my dog, walking the chalk downlands of home – the kind of landscape very often linked with an imagination of England that is forever 1940 – and have been remembering very fondly the veterans I was lucky enough to know, and, in some cases, call good friends.

Although I was interested in the Second World War when I was a boy, and it was still very much part of the daily vernacular, it drifted from consciousness when I emerged into my teens; to be honest, I was a pretty callow youth and don’t think I spent much time looking far beyond what was right in front of me. Rather, it wasn’t until I was playing cricket one day when I was twenty-nine, that I had my Damascene moment. I was batting when it happened, and standing by the umpire when the most incredible machine suddenly appeared far over mid-wicket, pirouetting around the sky with a deep-throated roar that seemed to change pitch in a way that was utterly seductive in way I had never before thought possible from an internal combustion engine.

‘What’s that?’ I asked incredulously.

‘That,’ replied the umpire in reverential tones, ‘is a Spitfire.’

Well, that was it. The following weekend, by chance, was the Flying Legends air show at Duxford near Cambridge. I asked my wife whether she wanted to come with me and fortunately she said no, she didn’t. It wasn’t that I didn’t want her company – of course I did – but I also knew she’d be looking at her watch and wanting to go way before I was ready. Without her, I had licence to be a new warbird nerd on my own.

Needless to say, it was utterly fabulous. I spent the morning walking the flight line, getting used to the different shapes of these amazing machines, whether Spitfire, Mustang or Thunderbolt, and perusing the mass of bookstalls. At one, I picked up a copy of Spitfire Pilot, by David Crook. It was a first edition of a memoir first published in 1944, and about his time with 609 Squadron in the Battle of Britain. Crook’s squadron had been based at Middle Wallop – the closest RAF Fighter Command airfield to home. Clearly, it was meant to be. Clutching this, I later watched all the flying that afternoon. It was mesmerising, captivating, thrilling, and as exciting as anything I had ever witnessed. I was hooked. Line and sinker.

At the time, I was working in the PR department at Penguin Books but longing to move back to the chalk landscape of my boyhood. I couldn’t think of any other way of getting there other than to try my hand at writing. After all, I arrogantly wondered, how hard could it be? I got up early each morning to write a chick-lit novel, which were all the rage at the time, and although I got a two-book deal, it wasn’t enough to give up the day job. And writing was, of course, far harder than I’d appreciated before first putting pen to paper.

On the other hand, I had cut my teeth on this early foray, gathered some great advice and writing tips along the way and learned a fair amount about the craft. By now, though, I had become obsessed by World War II and specifically, Spitfires, those who flew them, and the Battle of Britain. Like a lot of fellows, I’ve a slightly obsessive character and I now wanted to know everything I possibly could. And I also started to plot out a new novel: one of friendship, love, loss and war – and, of course, Spitfires. It would be Evelyn Waugh-meets-Birdsong-meets-Band of Brothers – but with a backdrop of the Battle of Britain. It eventually became a novel called The Burning Blue, and had a bit of North African desert and Cairo thrown in too. I absolutely loved writing it but I also became totally immersed in the research and that meant writing off to lots of former Battle of Britain pilots who had lived through that extraordinary summer of 1940.

Suddenly, envelopes addressed to me in lovely old-school handwriting started dropping onto the doormat, all of which were a very welcome change to the normal fare being delivered. Almost all those I wrote to agreed to meet me but the first two were Allan Wright, who lived in Devon, and Geoffrey Wellum, whose address was the tiny fishing village of Mullion on the Lizard peninsula in Cornwall. It was February 2001 when I drove down there to meet them. Both men had been in 92 Squadron, based at Biggin Hill from September 1940 onwards. Back in May, the squadron had also flown over Dunkirk; their commanding officer, Squadron Leader Roger Bushell, had been shot down and captured in their first combat flight over the beaches. Bushell later led the Great Escape and was then executed for his part in the mass break-out.

I’d also seen both Geoff and Allan on a 2000 sixtieth anniversary programme on Channel 4 called simply, ‘The Few.’ It was just them as talking heads, plus Tony Bartley, Pete Brothers and a couple of others, recalling their experiences in front of a pure white backdrop and interspersed with archive. To my mind, it remains one of the very best documentaries ever made about the Battle of Britain but I remember when I first saw it that I was struck by how young Geoff looked; well, he was comparatively so – just 78 at the time of filming. He sounded young too – his voice hadn’t aged.

In that February of 2001, he had written to suggest we meet in his local pub, which we did, and over several pints he told me his story. How he’d been only 19 during the Battle of Britain, that the others had called him ‘Boy’ and that they’d been drunk every night. Then every morning they’d trooped down to dispersal, cat-napping until scrambled. He’d prayed hard every day, pleading with God to spare him. Other memories, especially vivid, were of the morning dew on his flying boots, the clang of spanners, and the adrenalin surge when they were scrambled. The sheer terror of confronting overwhelming numbers of enemy aircraft. At one point he picked up an ashtray and also my pint. ‘So, here I am in my Spitfire, and here’s this bastard one-oh-nine.’ Then he played out the action. I watched and listened open-mouthed. It was heady stuff to a young thirty year-old, very green about the gills and largely new to this intoxicating moment in history.

After lunch, I went back to his house. It was tiny and it was clear he was pretty hard up. Life had been difficult in recent decades. Back in the early 1970s, he’d gone through a messy divorce, lost everything and had sat down to write about a time ‘when I’d done something useful.’ It was a kind of memoir, he told me. He had the manuscript somewhere and he promised to try and dig it out. ‘There’s a chapter which is really a typical day in the life of a Battle of Britain pilot, which you might find useful,’ he told me. ‘I’ll send it to you.’

I then went on to see Allan Wright the following day, who was softly spoken, self-effacing but utterly lovely. He had an incredible photo album, with beautifully written captions underneath each. They were all so young. Many of them had been killed in the Battle of Britain or later in the war. There were even pictures of Geoff – or ‘Boy’ as he had been then. He looked barely his nineteen years. During our conversation, Allan told me about the squadron’s first flight over Dunkirk. His best friend, Pat Learmond, had been killed that day – the same mission in which Roger Bushell had gone down. Allan told me he had got on with things the rest of day, flying a second time that afternoon. Only when he’d returned to the mess that night, and to the room he’d shared with Pat, and seen the still-damp, crumpled towel his friend had used earlier that morning, did the enormity of what had happened strike him. ‘That night,’ he told me, ‘I had a bath and suddenly completely broke down and wept – in a way I never had before or have done since.’

Allan I stayed in close touch and I met up with him and his equally lovely wife for some years after, but it was Geoff to whom I became rather forged – and in a way I had never imagined during that first meeting.

On my return home – at that time in London – I wrote and thanked Geoff and asked him about the chapter he’d mentioned. ‘Actually,’ I wrote, ‘if it’s not too much trouble, I wonder whether I might be able to read the whole thing?’ I offered to pay to have it photocopied and for the postage and so on, but to my amazement, a few days later the entire manuscript arrived. And not a copy, but the original – all neatly typed but with Geoff’s annotated notes and corrections in pencil dotted across it.

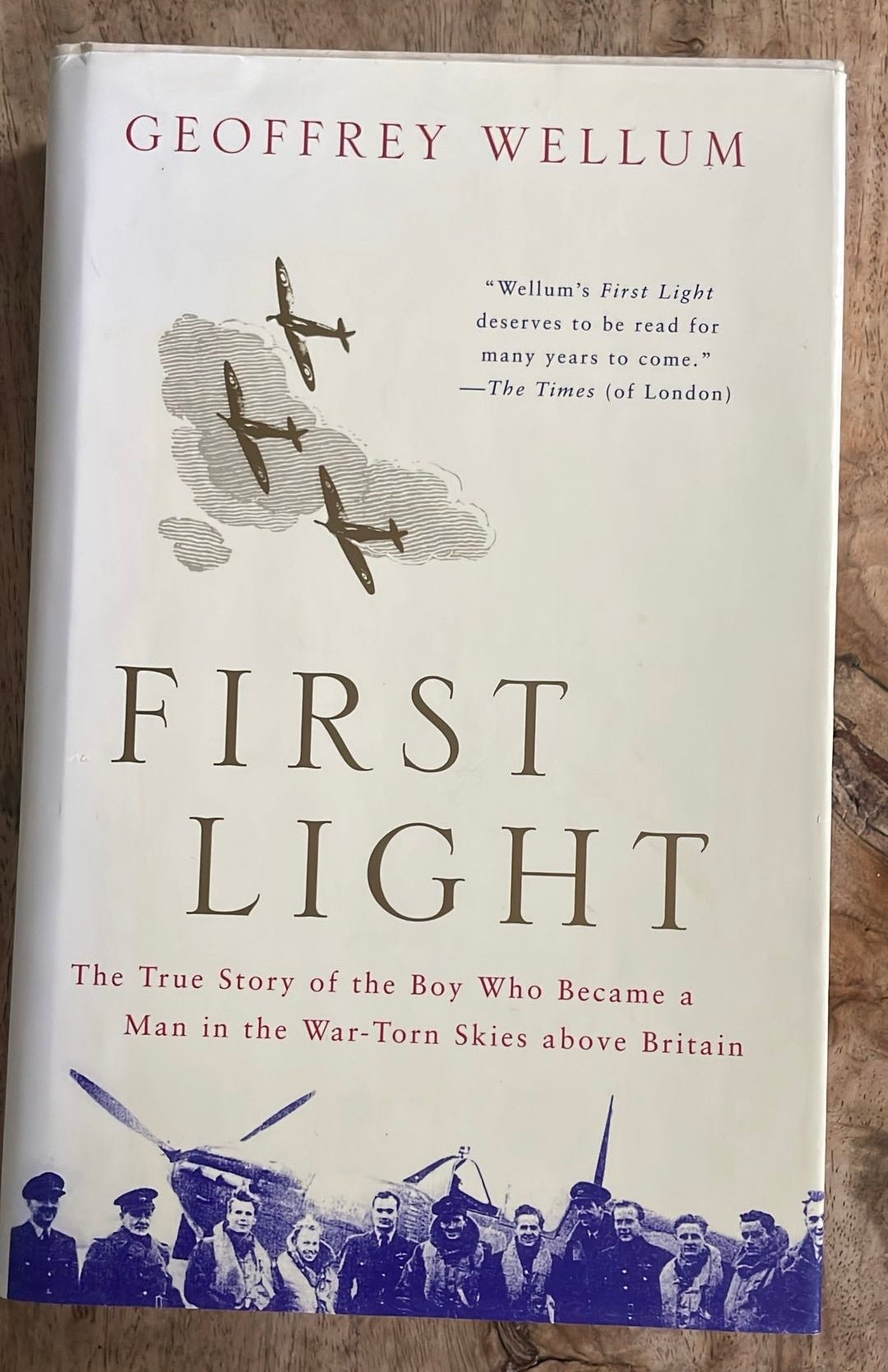

I didn’t have to read too many pages to realize that this was something very special indeed. Geoff was a naturally gifted writer; and he was writing for himself rather than an audience. The studied ‘dear reader’ tone and insouciance of many such memoirs was entirely absent. Rather, it had an incredible freshness to it and honesty. I’d never read anything like it and once completing it, rang Geoff and told him how wonderful I thought it was. I also told him I worked at Penguin – something I’d not mentioned when I’d met him – and offered to put it the way of one of the editors.

‘I didn’t even realize Penguin still existed,’ he said. ‘What the heck. Why not?’

I showed it first to my great friend, Rowland White, then to another close friend and colleague at Penguin, Eleo Gordon. She was fresh from the triumph of publishing Antony Beevor’s Stalingrad (for which I had handled the PR) and like me, loved Geoff’s memoir, which he’d called First Light. At an editorial meeting she urged her colleagues to agree to make Geoff an offer. This needed to be signed off by a senior publisher who was about to go on holiday over Easter for three weeks, so there was an urgency to me getting hold of Geoff. I rang him at home but he wasn’t there; my wife then suggested I try the pub in Mullion, which I did, and a smart idea that had been because sure enough, he was there that lunchtime, propping up the bar. The landlord passed me on. When I told Geoff that Penguin wanted to buy his book, he was dumbfounded.

‘Bloody hell!’ he exclaimed, then again, ‘Bloody hell!’

So, the deal was done, and before Easter 2001. It was a modest advance payment on projected sales, but actually worked out for Geoff because when it was duly published it sold exceptionally well. This meant he very quickly earned out on the advance and could start benefitting from royalty payments. In fact, the book was so well received - and remained in the bestseller lists for eons - that it went on to become the bestselling work of military history in the UK that decade. And it transformed Geoff’s life. From being one of the lesser known of the Few, suddenly he was elevated to superstar status. He had money in his pocket, bought himself a smart car, moved house, was feted wherever he went and certainly appreciated for being ‘useful’ back in 1940. Helicopters were sent to Cornwall to take him to VIP events, whether dinners in London or passing out parades at RAF Cranwell. It was so wonderful to witness.

Geoff was always extraordinarily grateful to me but as far as I was concerned, he owed me nothing. It was just an amazing piece of serendipity; anyone in my position, working at Penguin at the time, would have done the same thing. His book was stunning and would not have done half as well had it not been so beautifully written. It is amazing, though, to think that it sat, unread, in a drawer for more than twenty-five years.

But I do most definitely owe a debt to Geoff. During that first conversation in the pub, he also told me about flying from HMS Eagle to Malta in August 1942, part of Operation PEDESTAL, the last-ditch attempt to relieve the siege of that tiny Mediterranean island. I was new to this vast subject of the Second World War and while I’d vaguely heard of Faith, Hope and Charity, the biplanes that had defended Malta at the start of the siege, and also that the entire island had been awarded the George Cross, this was the limit of my knowledge. Geoff’s experiences there made we want to find out more. It led me to writing my first work of non-fiction – my first history book – which was bought both sides of the Atlantic, and which finally enabled me to throw in the towel with Penguin and move back to Wiltshire.

So, that conversation back in February 2001 in the pub in Mullion was a big moment in both our lives. I’ve been a historian ever since and now have nearly twenty history books to my name, not including a dozen Ladybird books on the war, as well as a dozen novels. I’ve been immensely fortunate. The publication of First Light, still rightly regarded as one of the finest memoirs to have emerged from the war, also transformed Geoff’s life.

Geoff and I remained good friends. I’m a regular visitor to Cornwall and we always made a point of meeting for a beer whenever I was down. We also hooked up at various functions and we’d also speak on the phone reasonably regularly. I wrote a young adult novel about the Battle of Britain then a major work of history too. I also made TV programmes; Geoff was in the BBC one I made back in 2010 and always part of my thoughts when I was writing about 1940.

At times he found the attention wearing and in his final years he did retreat a little. He loved Mullion, loved the sea and loved Cornwall. He was modest and humble to the last, but also always great fun; he had a terrific sense of humour and had got to stage in life where he didn’t care what others thought; he certainly called a spade a spade. I remember going on the Chris Evans Show on BBC Radio 2 with him one time. It was clear Chris had not been briefed; he literally knew nothing about Geoff, nothing about the Battle of Britain nor what it was like flying over southern England at that time. I could hear Geoff’s frustration and mounting incredulity that anyone could be quite so obtuse. He wasn’t rude; but I knew Geoff well enough to know what he was thinking. Actually, it was hilarious and we both laughed about it afterwards.

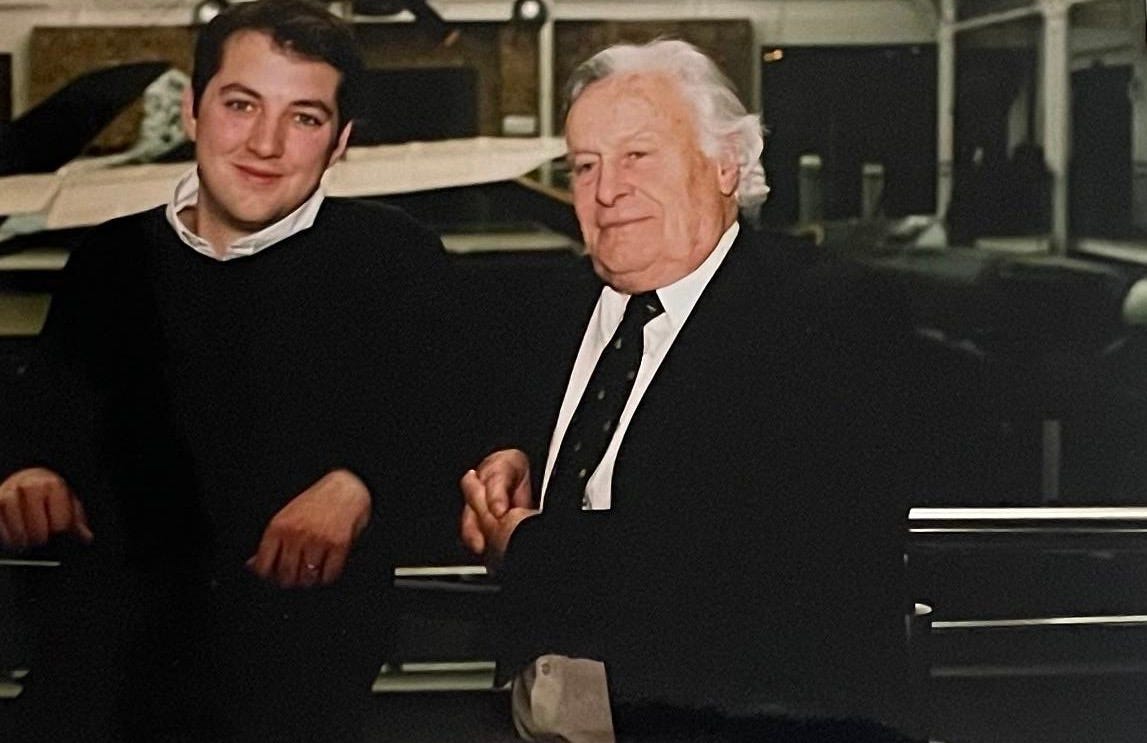

Paddy Hemingway might have marked the end of the Few this week, but thinking about him and the passage of time this week I’ve realized that for me, the moment of sadness – of grief, actually – came back in the summer of 2018. I was very fond of lovely Allan Wright but my other great friend amongst the Few was the wonderful Tom Neil. Both Tom and Geoff died within a couple of weeks of each other, that summer nearly seven years ago. Around the same time a documentary feature-length film came out called, simply, Spitfire. It’s beautifully shot and profoundly moving and I was lucky enough to see it on a large screen in a cinema. Tom and Geoff had just died and yet there they were, on giant screen, their respective characters bursting off the screen. I don’t mind admitting, I had tears running down my cheeks when I saw them; I just couldn’t help it. It seemed so impossible that they’d gone. They’d been such an important part of my life for nearly twenty years; it felt like such a significant moment. A marker in the sand. I’m sorry the Few are no more, but if I’m honest, I think I did my grieving a few years ago. This week, though, it’s been good to think back, to remember, and to cherish the friends I had and to remind myself, afresh, what truly extraordinary people they were. I’ve still got a manuscript copy of First Light somewhere but a couple of days ago I also fished out my hardback copy and found an old photo: of Geoff and me in the Imperial War Museum, taken in front of the Spitfire hanging over the atrium. What a privilege it was to have known him.

Mr. Holland, it is 8:15 in the morning my cat, Maggie Mead, is crying at my closed bedroom door. I should get up and feed her, but the chill of the morning coming in the window and the warmth of my comforter keeps me snuggled in bed.

I picked up my phone to check email and your post on the Few caught my attention. I grew up in the south east United States. My dad, my uncles, and my granddad all joined up and fought in WWI and WWII. My granddad Alfred, who was from South Brent, in Devon, immigrated to Canada in 1910, and joined up and returned home at the outbreak of WWI. He was badly wounded and ended up having his leg amputated after Battle of Vimy Ridge. My Uncle Frank, joined up after being a CCC Boy in Western U. S., he was wounded on D Day. My dad, served in Korea. He was at the Battle of Inchon and the things he saw changed him forever. He committed suicide at Fort Bragg, just before I was six.

I grew up hearing the men in my family talk, with voices quiet and solemn of friends lost and of terrible memories. As a girl, it was not considered appropriate conversation for me, but I would often pretend to be reading or playing just to be able to hear their stories. They didn’t get together that often, but I will always treasure my memories of when they did.

I don’t glorify war, but I am thankful for the men and women who fought so hard to defeat Hitler. Even more so now that my country is in such turmoil.

Your memories of the Few and in particular Geoff, brought me to tears. Your words made me think back on my childhood, and realise how much the men in my family meant to me. Thank you for sharing your memories of your friend, Boy.

James, such a lovely piece. Thank you. Resonance for me too. My father and some 40 WWII veterans I photographed and interviewed, mostly pilots + seven Ukrainian women partisans / combatants. I became friends with some of them and deeply felt their loss each time one of them passed away.

And of course it goes without saying the sound of a Merlin engine still gives goosebumps.